The Engineering Path Less Traveled

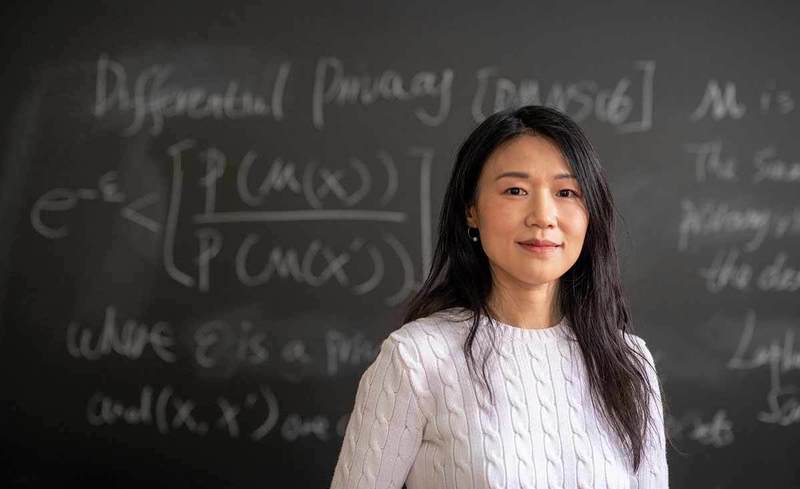

Jane Cleland-Huang

College of Engineering

Professor of Computer Science and Engineering

When Jane Cleland-Huang was 21, she left England to teach English in refugee camps in Thailand. The Vietnamese boat people there had suffered displacement, pirate attacks, rape and murder. Then she worked in Calcutta, India, again with the poorest of the poor.

Yet the memory she recalls most quickly is the time she taught a kite-building workshop for children. The next morning, driving to work, she was delighted to see dozens of bright little kites soaring above the refugee camp.

“So even in the midst of all their difficulty and suffering, they made the most of it,” said Cleland-Huang. “And life goes on. So I think that those experiences working in Asia, it kind of really shapes your perception of the world.”

“I feel motivated to do something that actually has the potential for making an impact in people’s lives.”

Cleland-Huang took a decidedly atypical path to become an expert and professor in computer science in Notre Dame’s College of Engineering. A self-taught programmer, she returned to school later in life and recently pivoted to research on how to program drones to work autonomously and safely perform complex tasks: search and rescue, fire surveillance, environmental sampling or medical delivery.

“Everything I do in terms of computer science and my research, I feel motivated to do something that actually has the potential for making an impact in people’s lives,” she said. “That’s why I like the area that I’m working in right now.”

Cleland-Huang lived in several places in the south of England growing up. She studied speech pathology at a university for a year before deciding it wasn’t her future. Instead, she went to Thailand and worked for about two years in two refugee camps, teaching English to children and adults who would resettle in English-speaking countries.

She met her husband, whose family was from China, in Thailand, and they began dating after she worked for three years in the slums of the Indian city now called Kolkata. He grew up in Chicago, but they stopped in Hawaii on the way home, where she took a job in a small private university. When the school asked her to work on a database project that involved global mapping, she “started to fiddle around” with programming at a time when “you have two big floppy drives.”

“I found I really like programming,” she said. “I decided to go back to school to learn to do it properly. I could definitely make my programs work, but I didn’t understand everything underneath.”

Cleland-Huang balanced raising three children in Chicago by staying close to home. She earned her undergraduate and master’s degrees at Governors State University and her doctoral degree at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She started her academic career at DePaul University.

“I was intent on having a teaching career, and then while doing my Ph.D., I actually found that I had the research bug,” she said.

That desire to expand her research led Cleland-Huang to Notre Dame in 2016. Her focus has long been in an area of safety assurance known as traceability, which she explains this way.

“When you build a system, you have to put together a safety assurance case to demonstrate that system is safe for use,” she said. “Traceability is part of that, and we use all sorts of machine learning and deep-learning techniques to connect pieces together that are needed to form this argument.”

For example, she notes that modern cars are controlled by software. Traceability involves identifying hazards such as collisions while changing lanes. The code behind the design to prevent that from happening must be tested rigorously and the steps must be connected so “you can create a rational argument that you’ve built a safe system.”

The software systems in cars or rockets involve private companies with proprietary designs, so Cleland-Huang decided building software for drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles, would be more practical. She began with a student project to build a mobile app people could use to request help, dispatching a drone to fly to the location.

“The drone side has taken on a life of its own now,” she said. “We’re not robotics engineers. We’re software engineering researchers, but we’ve been exploring some interesting questions in this new domain.”

Her team, including graduate students and summer undergraduate interns, met with the South Bend Fire Department to determine how drones could improve their lifesaving capabilities. The department already used drones for things like getting a bird’s-eye view of a fire.

“But we’re imagining — and we’re working towards — a different kind of vision, where the drones are actually smart, and the drones are considered real team players; they can make some decisions,” she said. “They can plan their own routes, and they can have on-board vision, and they can detect someone that you’re looking for.”

That work has led to those interesting questions “at the intersection of humans and drones,” she said. For example, would people accept a drone flying over their property if it was delivering a life-saving device as opposed to a pizza? The issues go beyond safety to incorporate psychology, philosophy, ethics, privacy and more.

“We’re not equipped to figure out these things,” Cleland-Huang said. “I think that’s why the largest scope of the project has to be multidisciplinary.”

Her team settled on river rescue projects as the best test case, mainly because current flying regulations require the drone to stay in the line of sight. But the capabilities of the latest (very expensive) drones are endless. Since drone-related lab-work was difficult during the pandemic, Cleland-Huang has focused recently on her roots in safety assurance, planning for potential product spinoffs.

“There’s a huge gap between prototyping something basic and getting it to work in a safe way,” she said. “It doesn’t sound like you’ve done much when you make it better, but it’s a huge amount of work to go from ‘We can fly this drone in a little demo’ to ‘We can do that reliably.’”

Other Stories